William H. Calvin, A Brain for All Seasons: Human Evolution and Abrupt Climate Change (University of Chicago Press, 2002). See also http://WilliamCalvin.com/BrainForAllSeasons/Soss.htm. ISBN 0-226-09201-1 (cloth) GN21.xxx0 Available from amazon.com or University of Chicago Press. |

William H. Calvin

University of Washington |

|

We’ve

gone from part of the Kalahari Desert, the part with a lot of water

passing through and evaporating in Okavango Delta, to a more typical

desert farther to the west, one with ephemeral streams lined with a few

trees – and almost none elsewhere.

It’s a savanna strip.

Admittedly, this was a good year for rainfall, but even when it

is much drier, the oryx, eland, and springbok (you really have to see

the youngsters’ jack-in-a-box act to appreciate the name) thrive here

on the valley floors among the sand dunes.

When you fly low over the area, you see a series of dark lines

stretching across the light desert floor.

They are dry watercourses.

There is still some water beneath the surface and, even if there

isn’t, the nearby plants are good at storing water for the rest of

the year. The leaves of

some plants can be crushed and wrung out like a washcloth, yielding a

surprising amount of water.

When the South African paleontologist Elisabeth Vrba told us

that there were a lot of new species of antelope appearing back about

2.7 million years ago in southern Africa, one of its prime implications

was that it indicated a need to adapt to arid environments.

And today, there are amazing numbers of oryx and the even bigger

eland here in the Namib Desert, happily grazing.

There are some small antelope that can forego visits to the

waterhole entirely, getting enough water from the leaves they eat.

If we could test antelope for landscape esthetics, they’d

probably prefer to look at something like a bush airstrip – a cleared

area where predators can’t hide.

And so bush pilots coming in for a landing have to first buzz

the airstrip, to chase them away.

It makes me realize how much meat on the hoof there was for our

ancestors to have exploited in arid environments.

If the antelope and the desert elephant hereabouts can adapt to

the desert, then they may make it possible for their predators to do so

as well. They just have to

patrol the strips, like teenagers cruising those urban strips following

highways out into the countryside. All

the resources are along a track, and it’s just back and forth.

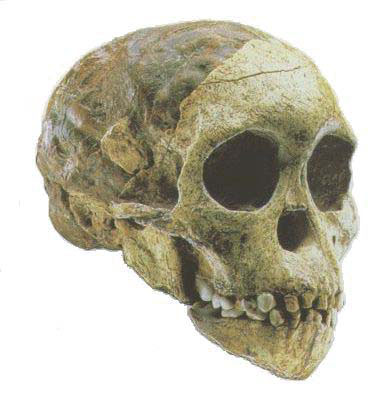

The fauna associated with the small-brained australopithecine

fossils indicate a wooded environment; they wouldn’t have liked it

here. The later versions

called Paranthropus between 2 and 1 million years ago were

sometimes found in wetland environments, as were the earliest Homo

species. It’s Homo

ergaster/erectus and later species that are found in extremely arid

and open landscapes like this. It

seems pretty clear what they were eating; certainly in South African

coast archaeological sites, there are a lot of eland bones. This

place is a desert because, at these southern latitudes, the

rains come from the east. And

by the time that they have traversed the whole width of Africa from

east to west (we’re just inland from the west coast), it is even more

of a rain shadow than Botswana’s Kalahari Desert.

Namibia is one of the driest places on Earth.

Indeed, what moisture Namibia gets often comes from dew, thanks

to the fog drifting in off the ocean, much the same as in the coastal

regions of Peru on South America’s west coast.

And there is fog here because the cold Benguela current offshore

causes the sea breezes to drop below the dew point as they blow in over

the cold current.

This cold current is part of the developing story

about how ocean currents and winds rearranged themselves just before

the ice ages started. Strong

winds often sweep surface waters aside – I’ll get into the subject

when I fly home over the North Atlantic and discuss the conveyor belt

for salt and heat – and bring deeper waters to the surface.

Deeper waters are cold; they’re also loaded with nutrients,

and so when they get brought up near the surface where sunlight can

penetrate, they serve as fertilizer for all the sea life offshore, a

whole food chain worth (lots of seals and dolphins and fishermen

hereabouts).

Well, at drilling site 1084, less than an hour’s flying time

west of here, the surface waters are about 10°C colder now

than they were 3.2 million years ago.

That means some stronger winds have developed in this part of

the South Atlantic Ocean. The big changes were between 3.2 and 2.1 million years ago,

in the second half of the Pliocene, just before we start talking about

the Pleistocene’s ice ages. They

go in lockstep with the changes in the North Atlantic. It’s all part of the story about how the ocean and

atmospheric circulation rearranged themselves, to plunge us into the

fickle climates of the ice ages. Which

we are still in. Just

to prepare you for hominid fossil country (my next stop is South

Africa’s caves, then Kenya’s Rift Valley), let me suggest reading

an account of how hominid fossils have been found.

I’m particularly fond of Alan Walker and Pat Shipman’s The

Wisdom of the Bones which contains the following account of how the

first australopithecine came to scientific attention in 1924 and how it

was mostly ignored for the following decades.

I always tend to think of the Leakeys’ 1959 discovery of Zinj

at Olduvai Gorge as the first hominid skull discovery, but it was only

the first in East Africa (and in a stone-tool context).

The Taung skull was actually discovered a quarter-century

earlier by workers in a South African quarry, but dismissed by experts

as some sort of ape: It

is a classic story of anthropology, all the more engaging for being

true. With unerring

timing, the box with the missing link in it turned up as [Raymond] Dart

was dressing, in wing collar and morning dress, to serve as best man

and host for a friend's wedding. The

men from South African Railways who staggered up to the house that

summer day in 1924 left two large crates blocking the stoop shortly

before the guests were to arrive. Dart had them moved to the pergola,

where they would be out of the way, and left off dressing to find a

crowbar to pry them open. The

contents of the first box were uninteresting scraps of fossil eggshells

and turtle scutes (the bony plates that underlie the turtle's shell).

On the top of the rubble that filled the second crate, Dart

spied an extraordinary thing: a natural, fossilized cast of the brain

– an endocast. It was of some creature whose brain was about as big

as that of an adult chimpanzee. From

his work with Elliot Smith, Dart immediately recognized that this was

no ape endocast (unparalleled as that would have been), but one with

distinctly human anatomy. He

rummaged through the box frantically and found a piece of bone, covered

in rock, into which the endocast fit.

And then real life intervened.

The groom appeared, anxious that Dart should brush the dust off

his suit and struggle into his stiff collar; the wedding party was

arriving momentarily. Dart took these two precious pieces of our ancestry and

locked them in his wardrobe, reluctantly abandoning them until the

festivities were over. . . . Dart's precious find was not only overshadowed [first by the Piltdown hoax and then by Peking Man], it was literally abandoned – left, in its humble brown-paper-covered box, in the backseat of a London taxi by Dart's wife. It was recovered only after frantic searching. Dart gave up on plans to publish a monograph and returned home, discouraged and defeated. He gave up fossil work for many years and subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown. For years, the Taung child sat, forgotten, on Dart's colleague Gerrit Schepers's desk at Wits. . . .

|

On to the NEXT CHAPTER On to the NEXT CHAPTER

Notes and

References Copyright ©2002 by The nonvirtual book is Book's Table of Contents All of my books are on the web. The six

out-of-print books are again available via Authors Guild reprint

editions, |